Comets: from suspicion to science

Comets were historically considered heavenly messengers or harbingers of doom. Our views of comets may have changed over time, but we continue to be mesmerised.

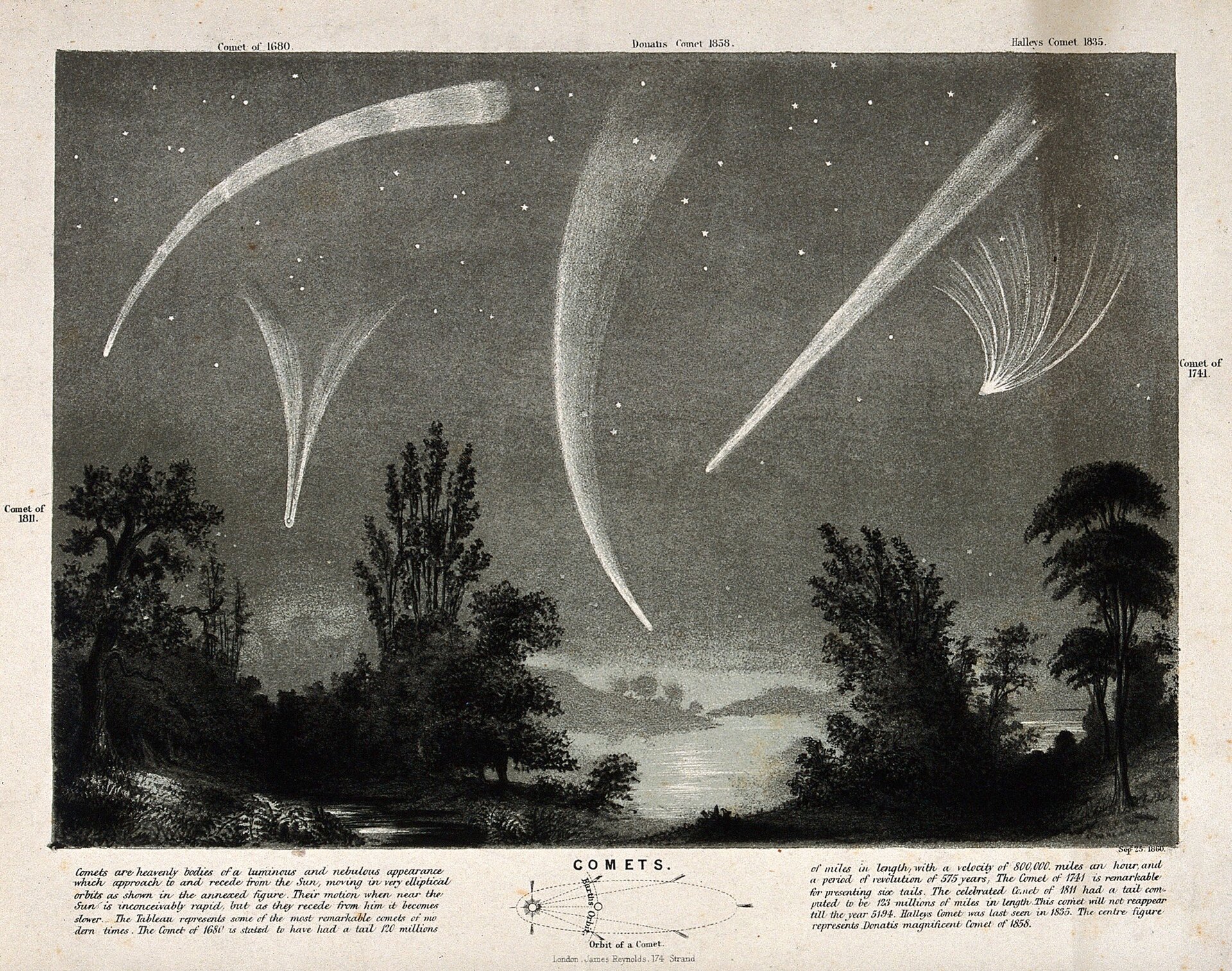

As celestial phenomena go, comets are impressive: bright blotches of light with long, beautiful tails, suddenly appearing to blaze across the sky before fading away just as unexpectedly as they arrived. Comets’ present-day name stems from around 500 BC, when Ancient Greek philosophers started referring to them with the word komētēs, meaning ‘wearing long hair’.

Humans have probably been captivated by comets longer than any archaeological record can testify. Early rock carvings resembling comets have been found in Scotland dating back to the second millennium BC, and a comet-like shape found on rock carvings in Val Camonica, Italy, dates to the late Iron Age.

Portents of doom

Rather than being viewed as beautiful and intriguing, comets were long regarded as omens.

Ancient Chinese emperors employed observers specifically to watch for comets, for they might reveal the ‘will of heaven’. They kept the most complete body of ancient observations of comets ever found, dating back to the 11th century BC. A Chinese book called Divination by Astrological and Meteorological Phenomena from the Western Han Dynasty (202 BC–AD 9)is the first known illustrated catalogue of comets. Each comet picture has a caption that describes an event its appearance was believed to have heralded, such as ‘the three-year drought’, ‘the coming of the plague’, or ‘the death of the prince’.

Around the same time, the Greek philosopher Ptolemy claimed that comets ‘show, through the parts of the Zodiac in which their heads appear and through the directions in which their tails point, the regions upon which misfortunes impend.’ Writing two centuries later, the Roman astrologer Marcus Manilius reported in his Tetrabiblios that comets could be blamed for everything from failed harvests to plague, wars, insurrection and even family feuds.

This superstition prevailed throughout the Middle Ages. It is immortalised in the Bayeux Tapestry, which commemorates the events leading up to the Norman invasion of England in 1066. Comet Halley is clearly depicted in the sky, being seen as a bad omen by observers in England, while Duke William of Normandy saw it as a positive sign from heaven. William invaded England, defeating the Anglo-Saxon King Harold. He was crowned King of England by the end of that year.

Comets return to science

In the West, beliefs about comets were influenced for more than two thousand years by the Greek philosopher Aristotle, who declared in the fourth century BC that comets were ‘windy exhalations’ from Earth that reached out into our atmosphere. Aristotle believed that the Sun, Moon, planets and stars revolved around the Earth on perfect spheres of pure crystal, leaving no room for unpredictable comets. Viewing comets as atmospheric phenomena made it easier to connect their appearance to earthly – and unfortunate – events.

Our understanding of comets experienced a dramatic leap forward with the appearance of the Great Comet of 1577, which was as bright as Venus and boasted a tail that stretched over a patch of sky some forty times the diameter of the full Moon. This offered Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe a unique opportunity.

Observing the comet from Denmark, Brahe noticed that its position in the sky differed very little from similar measurements performed by other astronomers across Europe. If the comet was something in the atmosphere, its apparent position should depend on which location it is viewed from. Seeing as this wasn’t the case, Brahe deduced that the comet must be at least four times farther than the Moon.

This started a new era of inquiry about comets, planets, and the fundamental physics that governs their motions. Galileo Galilei’s telescope observations and Johannes Kepler’s laws of planetary motion made it clear that not Earth, but the Sun lies at the centre of the Solar System. Isaac Newton published his universal theory of gravity in 1687, cementing this view in a firm theoretical foundation.

Soon after, Edmund Halley used Newton's theory to calculate the orbits for several comets – some of which he had observed during his lifetime, and many more that he had retrieved from ancient records. He deduced that the comet he had seen in 1682 was in fact the same one observed by others in 1607 and 1531. He predicted that this comet – now called Comet Halley in his honour – would appear again in 1758. Halley died before he could view it with his own eyes, but others were able to confirm his conjecture and, with it, that comets orbit the Sun just like planets do.

The last comet hysteria

In the last three centuries, we have continued to study comets with more elaborate equipment. Observatories were erected and equipped not only with larger telescopes, but also spectroscopes that can detect what chemical compounds are present inside the comet.

That is not to say that comets were popular throughout this time. As recently as 1910, Comet Halley’s reappearance led to mass hysteria thanks to the detection of cyanogen, a deadly poison, in the comet’s tail. The media jumped on French astronomer Camille Flammarion’s statement that the cyanogen ‘would impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet’.

As a result, protective ‘comet pills’ were sold, people bought gas masks and attempted to seal off their houses, churches held all night prayer vigils, and some even believed that the comet would cause the Pacific Ocean to sweep across the Americas and empty into the Atlantic. Luckily, this apocalypse did not come to pass.

Exploring ancient comets

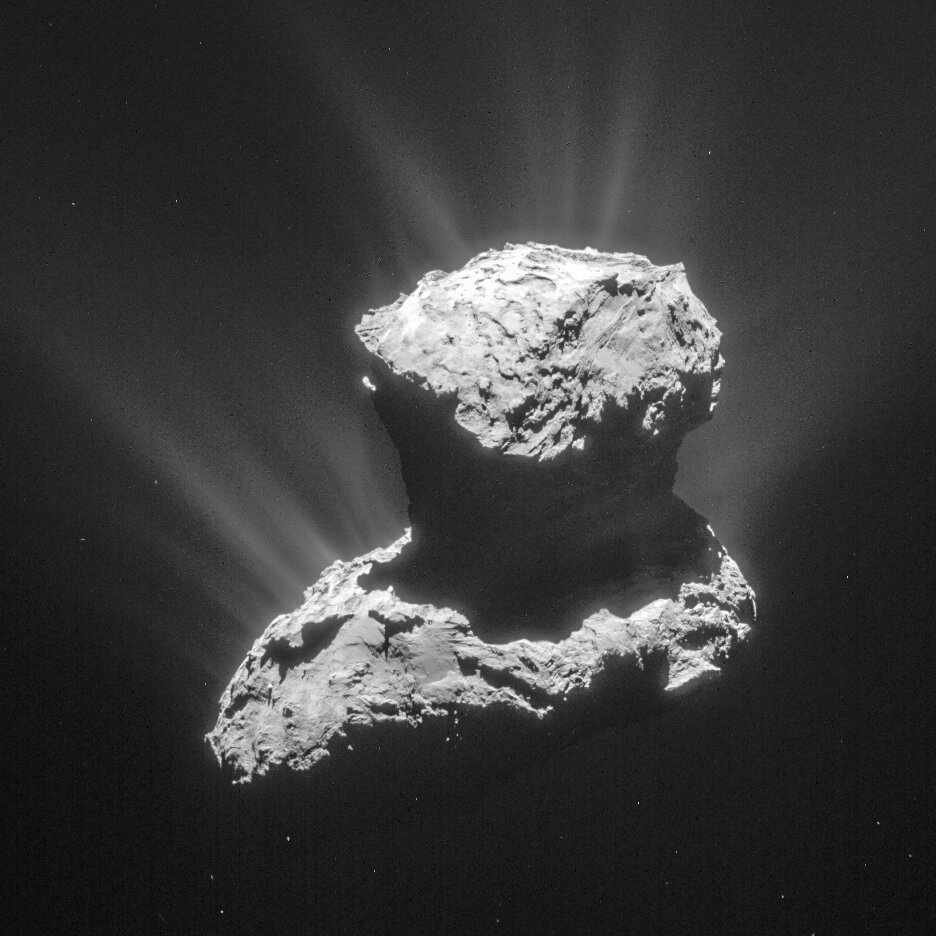

Our growing database of astronomical data allowed us to delve into comets’ physical nature, demystifying what they’re made of. In 1950, American astronomer Fred Whipple proposed that comets’ cores are structured like ‘dirty snowballs’. Today, thanks to data from space missions that have flown right up close to several different comets, we know that Whipple's model was fairly accurate. A comet nucleus resembles a fluffy snowball, usually only a few kilometres across, coated with a crust of dark material and spouting jets of vaporised ice.

Knowing what comets are made of is important, because ancient comet impacts may be responsible for bringing water and organic chemicals that are important to life to Earth. Comets are thought to have formed about five billion years ago from the vast, rotating cloud of material that surrounded the young Sun. In those violent times, many comets crashed into the young planets. Craters caused by ancient comet and asteroid impacts can still be seen on the surfaces of the Moon, Mercury and many planetary satellites.

ESA’s Comet Interceptor is the first space mission hoping to get up close and personal with a ‘dynamically new’ comet, one that has never or rarely been close to the Sun before. This could be a long-period comet or a comet that formed outside the Solar System (click here to read more about different comet types). The mission will provide us with key missing information on the formation and evolution of the early Solar System, our blue planet and the life it carries.